The idea of producing a 4K, stereoscopic arch viz film against a tight deadline would be enough to send most architectural visualization companies running to the hills. Here’s how Neoscape did it – with a little help from V-Ray.

Could you introduce Neoscape?

Carlos Cristerna, Principal and Director of Visualization

Established in 1995 as a visualization firm, Neoscape has evolved into a full service creative consultancy with studios in Boston, New York, and San Francisco. Over the years, our team of passionate and curious problem solvers has created integrated visual campaigns for some of the biggest companies in commercial and residential real estate and design. Our objective is to create immersive storytelling experiences for our clients that spark understanding, kindle vision, and ignite buy-in.

What was the brief for Ba Dai Tou?

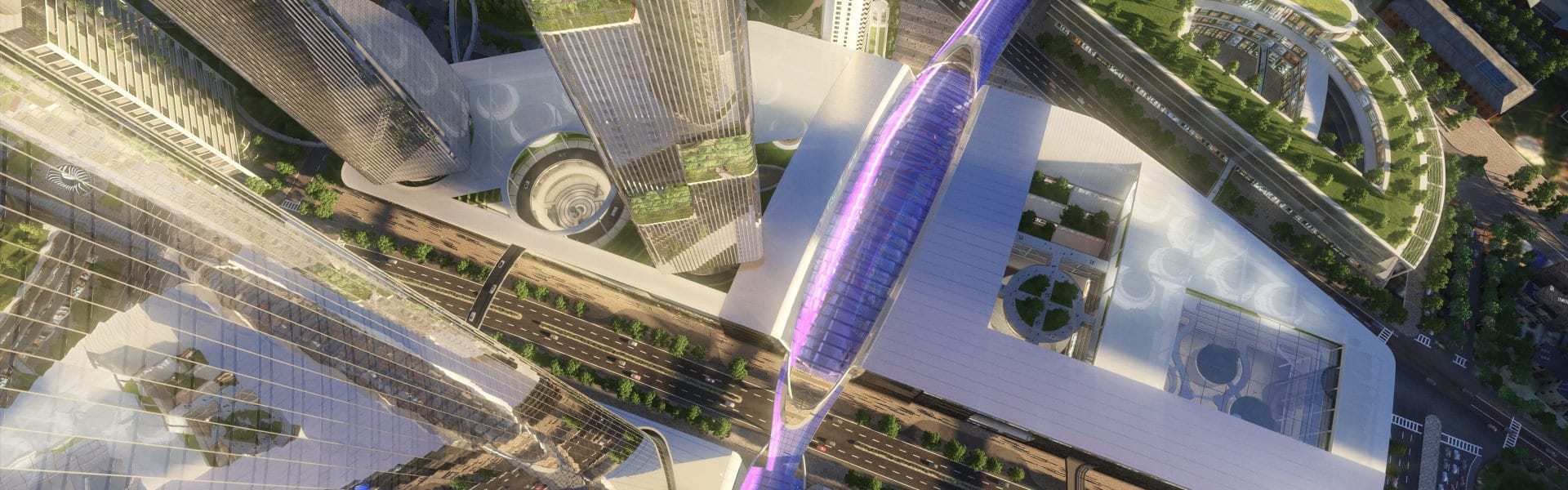

The client brief was quite simple: present the master plan design principles through its uses and users’ perspectives in an 8-minute, 4K film with a stereoscopic version. The architects, John Portman & Associates, had only preliminary design information at the time, but they did have in mind a clear hierarchy of importance for the project’s various components: pearl necklace (the pedestrian circle connector), dragon spine (the retail and project connector), riverside promenade, and the public spaces. They also suggested a film sequence that reflected this hierarchy which ultimately, as we pointed out, didn’t lend itself to a cohesive film narrative.

As the quality was much higher, did you have to plan in more detail?

Yes. We knew that we only had one chance to render the 4K frames. Reviews couldn’t be in 4K or in stereo since they were conducted via video conference with Boston, Atlanta and Shanghai (plus two translators). We had to carefully make sure that all of our work was complete and ready to go when we hit that final render button. To make that work, we rendered mostly everything in camera instead of post.

We rendered mostly everything in camera instead of post.

We also had to keep in mind that the film was going to be shown in different aspect ratios. The marketing center projection required a 19:4 aspect ratio for its 55' wide x 11' high projection screen. However, we had to go with a 16x9 version as the master film so that it could be viewed on conventional devices, and then crop to fit the bigger marketing center screen. We had to be very deliberate in our selection of camera moves and framing, making sure that they would work for both ratios. You’ll notice that most of the cameras pan from bottom to top, top to bottom, or have a subtle move to reveal the subject so no matter what ratio, you’ll still be able to see the totality of the shot as it was intended. It was kind of like a moving Ken Burns approach.

What influenced the look of project, in particular the neon wireframe sections?

When we put together the creative treatment, we knew that we didn’t want it to simply be a programmatic study like it always is. We wanted to take a more interesting visual style without over complicating the production as it was already challenging to do. To take that kind of film out of the equation, we came up with a more abstract way to tell that story. Since the dragon spine was already inherent in the design, we used it as our device to take the audience through Shanghai, up the river, and to the site — all of this being a symbol to the history of the project location, specifically as the historical point of entry to Asia. We took the traditional Chinese dragon of New Year celebrations and modernized it — with a little inspiration from TRON of course — to give the film a modern, vibrant feel.

Just like visitors from ancient China, we had originally planned a journey on a traditional Chinese boat up the river to experience the historic milestones that made Ba Dai Tou: its mountains, the river, the mill, and the area’s industrial era. We saw the boat as the abstraction of progress and the vessel that carries us and our characters (the users) to our destination. Unfortunately, this sequence didn’t make it into the final film, but we retained the boat and dragon as the devices that take the audience up the river and to the site.

How much rendering did you have to do?

32,500 frames were rendered in the final cut, excluding the neon sequence. This was only rendered 4k stereo at the end; the three preview reviews were rendered in 1080p 2d for practical purposes. We calculated that we would need 17.5 days of final rendering for 3D only (one computer would have taken 1,010 days). When we did this math, though, we realized that we already only had 12 days left! Fortunately, between V-Ray tools and a lot of flexibility, our average times were very good; some frames also rendered a lot faster than anticipated.

In what time frame?

Our timeline was 20 weeks. This included pre-production, creative, the eight-day practical shoot in Shanghai, production and post production.

How big was your render farm? And how did you manage it?

It’s a 100-node renderfarm with 200 processors and 1,000 cores, 2.5 THz processing power and 3 TB RAM.

We used Deadline to control the machines and prioritize renderings. Because we had planned for everything to be rendered in camera, and we had figured out how much time we needed to render, it was a fairly straightforward process.

The real challenge was updating anything in the 4k master edit. A small change would have us waiting a few hours to export and review in 2D and 3D.

What sort of optimizations did you have to do?

The nice thing about rendering large frames is that they are more forgiving with noise, so it really came down to saving smaller irradiance maps and lowering the noise threshold. While we were in Shanghai for the practical shoot, we tested the noise levels of a 1080p version of the film at the marketing center (on the actual screens) and found them to be acceptable, so it was clear to us that once we rendered the 4k version we would not have to worry about noise at all.

What were the average render times/frame?

1 hour and 52 minutes for the 4k stereo frames, to be precise. This was, of course, the average time we got from our data collection.

What were the challenges of delivering a project in stereo?

The biggest challenge is that you can’t see the film in stereo while you’re working on it, and so we needed to change the pipeline to review it in stereo. After these stereo reviews, we realized that we had to re-render some shots with ridiculous inter ocular distances to increase the depth, using it to greater effect as a storytelling device that will impact viewers’ emotions. For instance, it became clear that wide shots looked flat, and that shots looking up or down needed to be exaggerated to increase drama. So, after our first stereo screening we adjusted about half of the cameras to create a better experience.

Practical footage was another challenge, as we didn’t have a budget to shoot the B-roll and timelapses in stereo. Ultimately, we decided to convert the 2D shots to stereo in Nuke. Our very talented compositing crew made 40 shot conversions in a very short amount of time.

Have you seen the final project on the big screen?

Carlos Cristerna: Yes, but only I’ve seen it! It plays in the Shanghai marketing center. When we finished the project and viewed the stereo film in various formats here in Boston, it was clear that we would have to dial the color grade and exposure to work with the marketing center’s projection system. So, we went to Shanghai and delivered the film in person. We brought three different versions of the film with us, with slight variations in color, contrast, and exposure. We were also prepared to adjust on site with some LUTs if necessary. Fortunately, however, one of the three pre-backed options worked like magic, and the film looked great. After all this testing, we had a private screening with Jack Portman and his client that was very successful. It was a happy ending: the client was happy, his client was happy, and so were we.

What are you working on next?

Carlos Cristerna: We’re currently just wrapping up production of a film for an even larger project. It was done in less time than Ba Dai Tou (admittedly not in 4K or stereo), but it was a significantly bigger development.

We can’t wait to show you!